Climate change transforms high finance’s relationship with society

Extinction Rebellion’s city centre disruptions and Fridays for Future’s well attended school strikes across Europe inspired by Greta Thunberg have placed climate change firmly in the public consciousness. Now more than ever before, the question is not if something should be done, but when and how. Robert Blood, managing director of NGO tracking and issues analysis firm SIGWATCH, explains how this is already forcing the financial sector to take more decisive action.

In June 2018, Legal & General told Japan Post Holdings (JPH) that it was dropping the company from its $6.7billion Future World index funds. It added that any of its funds that still held shares would be instructed to vote against the re-election of JPH’s chairman. L&G justified the move by saying that JPH had “shown persistent inaction” to address climate risk.

L&G is not alone in taking action on climate risk. BNP Paribas, AXA, Allianz, RBS, Munich Re, ING, Rabobank, Standard Chartered, Barclays and HSBC are all now committed to exiting deals and investments concerned with coal mining and coal-fired power. In the U.S., despite (or arguably because of) an administration that is openly sceptical of the need for climate action, many of the largest banks including JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Citi, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have all announced coal exits, as they have begun to do in Australia. Japan’s largest banks and insurers, and their equivalents in Singapore and China, have come late to the divestment game but they too are finally rolling out new coal pledges.

Revival of campus activism

These moves are the consequences of growing pressure from stakeholders, driven by activist groups, for almost ten years. It was in 2013 that US student environmental groups first demanded college endowment and pension funds sell off their shares in fossil fuel-related projects. Their carbon divestment campaign was modelled on the Apartheid campus divestment battles of the 1980s, which aimed to undermine the economy of South Africa by forcing U.S. firms and investors to sell off South African assets. Congress imposed investment bans too. Until the Klerk-Mandela settlement of 1993, South Africa was for almost a decade a pariah state for investors.

While the priority for campaigners has been to drive out coal, the pressure on carbon does not stop there. Under the slogan, ‘extreme carbon’, campaigners have extracted concessions from leading financial institutions on Canadian oil sands, Arctic and deep-sea drilling, shale gas, and related infrastructure such as LNG terminals and pipelines. As these specific sources become demonized, conventionally produced oil and gas becomes more and more dubious. Divestment on the basis of increased risk has a tendency to become a self-fulfilling prophecy. When money flows out of an asset type, the remaining investors are by definition exposed to increased financial risk, and this in turn stimulates additional cycles of divestment. There is a reason why fossil fuels are commonly described by climate campaigners as ‘stranded assets’. Even giants like Shell are now openly reconsidering their futures.

The success of campaigners in getting their arguments heard and taken seriously is a relatively recent phenomenon. In fact, one of the most striking developments in the financial sector of the last decade has been the ‘mainstreaming’ of environmental and social responsibility standards in investing. Until relatively recently, these were the preserve of SRI and ethical funds, often funds that had been set up at the behest of well-funded environmental groups who insisted on strict exclusion criteria.

Now, environmental and social governance (ESG) is embedded in standard fund management practice, helped by pressure from political stakeholders and customers, particularly in relation to the institutions’ own funds, to take intangible risks such as human and indigenous peoples’ rights seriously.

Financial institutions’ increased willingness to listen

The financial crisis of 2008 also played an important part. With the reputation of the financial sector in tatters, leading institutions made a conscious decision to prove their ‘value to society’ by adopting ESG, and engaging with NGOs in a far deeper and more open way than ever before.

Campaigning NGOs have not been slow to exploit investors’ new-found willingness to listen, to push their wider agenda on a wide range of environmental and social concerns. These include human and indigenous rights, sustainability, corporate environmental responsibility and benchmarking, labour standards, animal rights, even the ethics of investing in industrial scale agriculture.

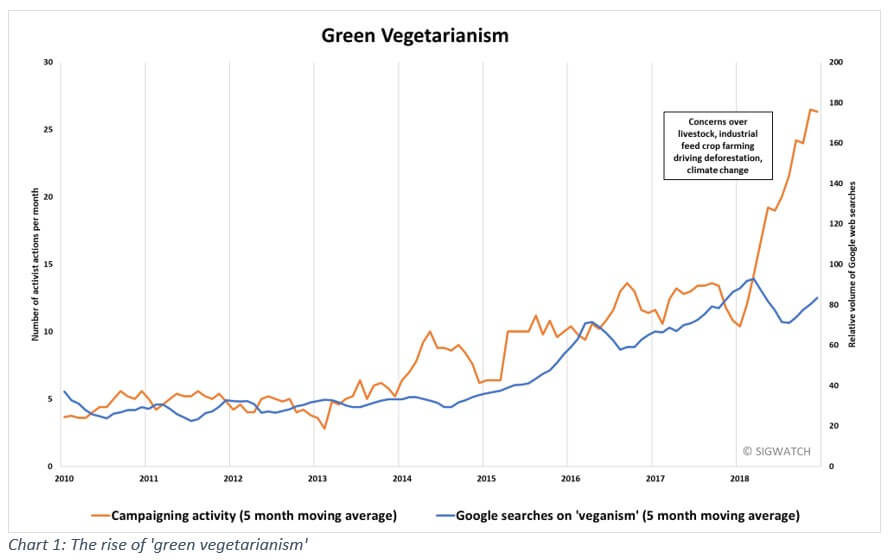

As NGOs become more active and more influential, their campaigning can provide an early warning system for emerging issues for investors. On plastics and shale gas (fracking), campaigning levels rose significantly ahead of public concern, anything up to 12 months prior. This is not very surprising, since activists are effective at getting media attention and this feeds into public awareness. We are now seeing this with ‘green vegetarianism’ – the switch away from meat for environmental reasons like deforestation and climate change (see chart 1). All these correlations show how campaigners can ‘make the weather’ politically.

It will become more important for global financial institutions, as they develop ever more expansive policies and standards under pressure from NGOs and other stakeholders, to track the long-term implications of the criteria they are enforcing.

Pension funds linked to ‘politically sensitive’ workforces such as public sector employees, health and education, are especially vulnerable to this kind of pressure. The campus campaigns of the carbon divestment movement quickly moved on to targeting staff pension funds once they secured the support of a significant number of faculty. In Denmark the state pension funds have been called out by Greenpeace on the same issue. In Sweden, Greenpeace launched a boycott of payments into the mandatory state pension scheme AP3 until it agreed to divest from all fossil fuels and related infrastructure projects.

ESG goes mainstream

With leading financial institutions engaging seriously with campaigners and their concerns, doing nothing is not an option. As more major mainstream funds are managed on ESG principles, investment managers and institutions increasingly have to justify to their peers why they are not doing the same, rather than the other way round. It is no longer a question of, Are the NGOs being fair, but rather, Do the NGOs have the ear of our stakeholders, and are they already influencing rival institutions? They may be small and apparently insignificant compared to a bank or investment fund, but NGOs have become critical players in transforming what society expects from finance.