Asset managers adopt new approach in era defined by automation, algorithms and big data

As soon as the financial crisis started to recede, Jordi Visser knew something had to change. Algorithms were starting to rule markets, and hedge funds like the one he managed were confronting a tougher era.

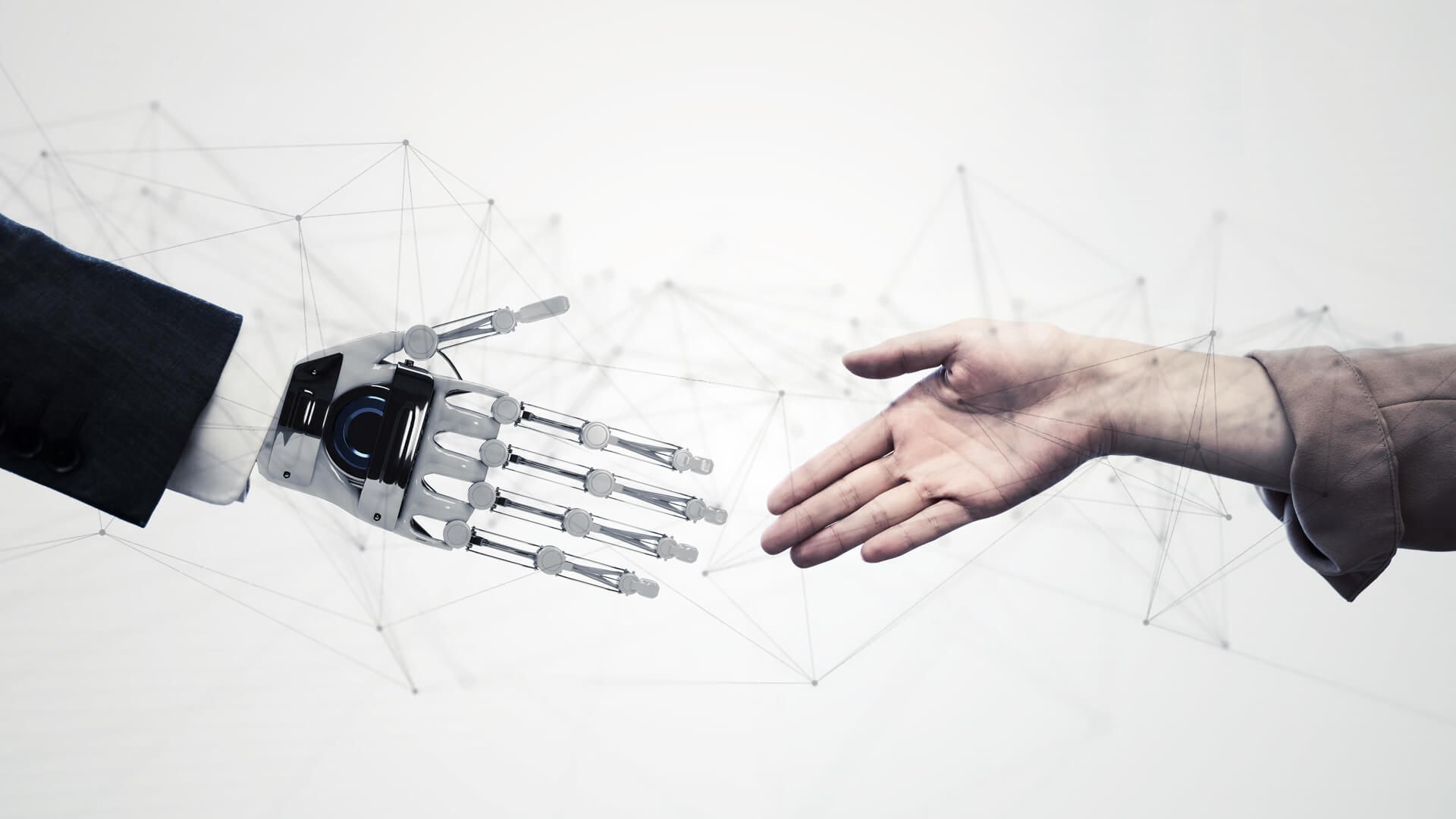

So Mr Visser, chief investment officer of Weiss Multi-Strategy Advisers, started to rethink how the $1.7bn hedge fund could survive in a less hospitable environment. The solution was to evolve and meld man and machine. “We are competing against computers these days, so we had to become more efficient,” Mr Visser said. Mr Visser and Weiss are not the only ones making some adjustments— with varying degrees of gusto — to a new investing era defined more by automation, algorithms and big data.

Analysts have dubbed marrying quantitative and fundamental investing “quantamental”, an admittedly ugly phrase, but one that many think will define the future of the asset management industry. These initiatives are proliferating across the investing world, from small boutiques to sprawling asset management empires. In January, JPMorgan’s $1.7tn investment arm set up a new data lab in its “intelligent digital solutions” division to try to improve its portfolio managers, rather than replace them entirely with algorithms. “It augments existing expertise. We don’t just . . . try to come up with strategies out of thin air,” said Ravit Mandell, JPMorgan Asset Management’s chief data scientist. “There’s stuff that happens in the human brain that is so hard to replicate.”

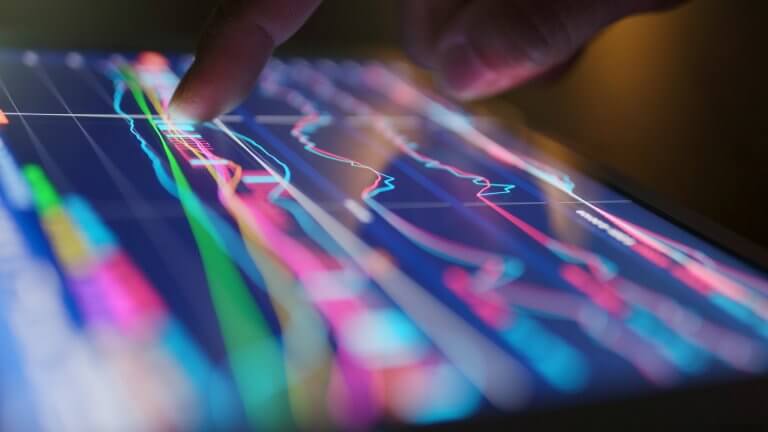

The 18-strong unit focuses on everything from automating and improving humdrum tasks such as pitch books and digital tools for customers, to more high-end demands such as product creation and improving JPMorgan’s investing prowess. The data unit has already used a form of artificial intelligence known as a neural network to analyse years of corporate earnings call transcripts to identify which words are particularly sensitive for markets, or might augur trouble.

That frequent uses of “great” and “congratulations” are generally good for a stock price, and talk of debt covenants and inventory overhangs are bad, might be obvious to any human fund manager, but they can only listen to or read a limited number of transcripts. A machine can scour thousands.

JPMorgan Asset Management’s data scientists are creating an alert system that will ping its portfolio managers whenever transcripts are particularly positive or negative, and voice analytics that mean they can even detect worrying signals in someone’s intonation.

Some investment groups are starting to use technology to spot well-known behavioural biases. For example, Essentia Analytics crunches individual trading data and looks for common foibles, such as fund managers’ tendency to over-trade when on a losing streak, or hang on to poor investments for too long to avoid crystallising losses. When that happens, fund managers get sent an automated but personalised email signed “your future self” reminding them to be aware of these pitfalls.

“A computer can remind you to follow your own process,” said Clare Flynn Levy, Essentia’s founder. “It’s like a little light on your car dashboard flickering to remind you you’re running out of oil.” Weiss’s chief data scientist Charles Crow has built something similar for the hedge fund: a digital “baseball card” system that analyses and ranks its portfolio managers according to 17 parameters, such as stale positions or movements in correlations, and alerts them to any issues.

In parallel, Weiss’s top managers have a dashboard to allocate money to various teams, showing which ones are good at timing, but poorer at portfolio construction, or are expert stockpickers but have sectoral biases. This helps Mr Visser monitor for hints of crowded trades. There are plenty of “quantamental” sceptics. Many pure quants are doubtful that traditional asset managers can master anything but the rudimentary, commoditised parts of their craft. Meanwhile, many traditional investors argue that it is an overhyped fad that is feeding shorttermism.

Recommended

Even fans admit that the cultural shift needed to fully embrace these new techniques by largely middle-aged investors is so significant that it could take years before the full potential of “quantamental” investing is realised.

“Behavioural change is the hardest part,” said Ms Flynn Levy, herself a former money manager. “I think an entire generation of fund managers have to age out of the industry before we really see big changes.”

Nonetheless, few money management executives doubt that technology will play an everincreasing role, and many are hopeful about the potential to invigorate the industry’s often patchy investment results.

For example, it appears to have helped Weiss last month, when many hedge funds were clobbered after having been sucked into technology stocks. Mr Visser declined to comment on performance, but an investor document seen by the Financial Times indicates that Weiss’s main fund sidestepped most of October’s torrid markets, and is up 6.3 per cent so far this year.

Mr Visser admitted that not all the hedge fund’s portfolio managers were thrilled at the new measurements, tools and expectations, but argued that the quantitative tools were fair, objective and necessary. “They either want to get better and embrace it, or they fight it,” he said. “But it’s a case of adapt or die.”

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018. All rights reserved